I Shall Purchase a Sword and Call It Kindness Clip Art

This article -- a compilation of 2 viewpoints on calculation authentic sword combat to games -- originally appeared in the December issue of Game Programmer mag. You can subscribe to the print or digital edition at GDMag's subscription page, download the Game Developer iOS app to subscribe or buy individual issues from your iOS device, or purchase individual digital problems from our store.

Eben Bradstreet on Existent Combat

The first time I walked into John Clements's Fe Door Studio, I learned how to concur a longsword.

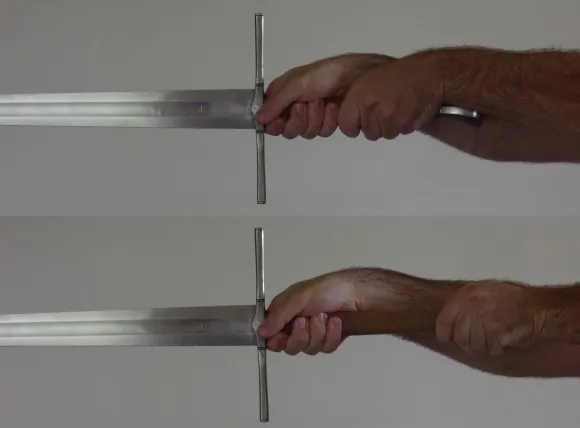

I thought it was obvious: Grip the handle with both hands. That'due south how I'd always imagined it was done. Information technology'south how they did it in the movies, later all. The handle is the comfortable flake between the pommel and the cross-guard. It's large plenty to accommodate both hands. And so I agree it there, right?

Wrong. The correct mitt (or the leading hand) indeed goes just beneath the cross-guard. The left hand should grip the weapon by the pommel -- that'due south the knob at the end of the handle -- in well-nigh circumstances.

At first, I was a little dubious. "Hold information technology there? Actually? I thought that function was merely for smashing skulls. Or remainder. Or ornamentation."

My mind drifted to Orlando Blossom in an early scene in Kingdom of Heaven, where information technology'due south quite clear that he grips his weapon in the way that seems about harmonious: by the handle, with both hands. Later in the picture, he fifty-fifty helpfully confirms my bias by smacking someone in the noggin with his hand-gratuitous pommel.

Figure 1: The proper style to hold a longsword.

The reality of the pommel is a little more complicated. Information technology is used to knock sense into your enemies, it does bear on the rest of the sword, and sometimes it's even pretty to wait at. But, it'due south likewise a not bad place to agree the weapon. And it's a perfect case of how all my assumptions about the sword were challenged when I beginning fix out to learn the reality of the weapon.

Grounding Fantasy in Reality

Every bit it turns out, how to agree the longsword is likewise a keen place to start talking near what that reality can mean for animators. If a video game graphic symbol grips the pommel with its trailing hand, the resulting animation volition have fewer bug with deformation around the wrist, less clipping between the sword'southward mesh and the grapheme's mesh, and volition display better biomechanics when cut (which we'll talk about later).

The first two points are subtle improvements, and are all-time demonstrated by gripping the handle by both hands, then extending the sword forward, holding the weapon at eye-level. From this position, kickoff turning, windmilling, and cutting with the weapon while keeping information technology in front of you. If you lot don't have a sword immediately bachelor, you lot tin can practise this with whatever wooden or plastic dowel. But concord the dowel roughly 3 to five inches from the stop in society to simulate the exposed pommel.

As you swing, pay attention to how often the pommel wants to intersect with your wrist, especially when you endeavour to drop the bract to the lower correct, and note that in some positions, y'all tin't continue an arc because your trailing wrist simply won't contort enough to facilitate the movement.

As I said, these are subtle points. The real magic happens when you now try the aforementioned thing, just grip the pommel, instead of the handle, with your left paw. The showtime matter you lot'll observe is simply how much more leverage you have. The sword is a lever, subsequently all, and your leading wrist is the fulcrum, so it makes sense that the further dorsum from the fulcrum you're able to grip, the more control you'll exert on the bract. You should also notice that this method is easier on your wrist (which volition assistance with deformation), particularly if you allow the pommel to slide and turn freely in your palm. Your wrist can now stay relatively directly through most swings, and there's no longer any danger of the pommel clipping through the wrist's mesh on your graphic symbol models.

Bad Sword, Bad Reference, Bad Animation

Inevitably, you'll want to capture some reference. Fifty-fifty if you're using move capture, it's always good practice to "feel" the movement yourself, or to whip out a camera and become through some of the motions.

The all-time way to not get good reference, no affair how you make up one's mind to agree the sword, is to employ a crappy weapon. For almost people, the easiest access they have to a generic sword is either through a catalogue, a renaissance faire, or even the odd novelty store. With the rare exception, the weapons you become from these sources are universally terrible for your animations -- they're oftentimes much also heavy and poorly counterbalanced.

Nosotros accept one of these weapons at my workplace, and even after two years of swinging steel as a martial art, I nevertheless tin't do annihilation with it. That weight transcends physical reality, and every skilled attempt to mitigate it directly influences how our characters move. It'due south an awkward and sluggish prop that makes our characters look equally bad-mannered and sluggish. Early on on, nosotros decided not to use information technology.

Instead of trying your luck with weapons that will harm your animations, it's almost e'er better to merely become to a hardware shop and purchase a wooden dowel, or a length of weighted PVC pipe. If you're feeling crafty, you might even want to make your ain wooden sword (historically called a "waster"). Wooden props like these will certainly be much lighter than steel, just they'll be easier to swing in a practiced way (adept for the director, the animator, and the player). The alternative is a poor knockoff that will devalue your results by virtue of your trying to utilise it, rather than merely hanging information technology up and staring at it (equally information technology was fabricated for). Bad swords make your job more than difficult than information technology has to be.

The weapons that John and I are using in these images are fabricated by Albion Swords (www.albion-swords.com). There tin be long waiting times for these weapons, and then it may non exist an platonic solution for gathering good reference quickly or cheaply.

All About Universal Biomechanics

As I learned more about the fine art of fighting with the longsword, equally Medieval and Renaissance Europeans understood it (and actually chronicled in dozens of report guides), I began to empathise how intuitive the whole skill set actually was. There are a few basic guards, roughly nine vectors of attack, and a scattering of rules that guide your footwork. The more avant-garde techniques, while impressive to expect at, are largely ancillary: In all the sparring matches I've seen, the flashier techniques are never used. In fact, the more I watched and the more I learned, the more it started to feel familiar.

That sense of familiarity didn't come from the movies or the phase -- and certainly not from the highly sportified world of foil fencing. No, the moves I was seeing in sparring matches, which were reflected in the historical imagery plastered on the walls around me in John's studio, looked more than like the close-quarters gainsay training nosotros'd done while I served in the Regular army, or mixed martial arts matches on TV. Information technology was savage and in-your-face. At that place was nothing at all pompous or chivalric about it. This stuff was real, and information technology was universal -- because no thing what time or place nosotros come from, we're all human being and we're all governed by the same biomechanics.

Consider the weapon nosotros've been talking near. If I had been handed this weapon three years ago and someone told me to swing information technology, I would have done what pretty much anyone would practise. Maybe swing it similar a baseball bat, or considering I used to cutting wood when I was kid, I might swing it similar an ax. If you were handed that weapon, what would you exercise? Y'all might endeavor to mimic what y'all'd seen Conan practise, or imitate a samurai.

What you wouldn't do (at least, what most of us wouldn't practice), is swing it similar a golf guild. But why not? Both are roughly the aforementioned length, both are used to hit things, and both do virtually of their business organization up to 5 inches from the end. Certainly, to swing a sword like a golf guild and connect would exist devastating to your target. So why don't we apply information technology that way?

The answer is biomechanics and perception. Biomechanically, it's not efficient: The target of a golf society is at ground level, where the target of a sword is at middle level. Because the difference in targets is then drastic, nosotros instinctively perceive that to swing a sword like a golf order is incorrect.

Now permit's use this idea process to delve a fiddling deeper: Think most the target of your animations, and where your character'southward enemies are located. Is swinging the weapon like a baseball game bat the solution? Consider the game yous might be working on: In an environs where your character is trying to kill people, the target of your swing is more than likely to exist the pitcher (in forepart of you), than the ball (side by side to yous at the moment y'all swing). Is it still right, then, to stand similar a batter, and swing equally though you're trying to hit the ball? Probably non.

So now we tin take a step back and ask ourselves: "What is the best practice?" Cypher beats calling in an expert, of form, just fifty-fifty if you don't take the time or resources for that, putting in a little effort in developing your fundamental understanding of human biomechanics with respect to weapons can help make clean up your animations in a major way.

Realism Plays Well with Your IK Rig

As I stated before, the nuts of Renaissance fencing and martial arts (the discipline we call "MARE," or Thouartial Arts of Renaissance Europe) are pretty straightforward, and once you understand them, the rest becomes a matter of relentless conditioning and practice.

For the purpose of the animator, yet, the basics can be a great starting indicate that will requite your warriors a unique visual silhouette, without requiring the animator herself to become a scion of martial prowess.

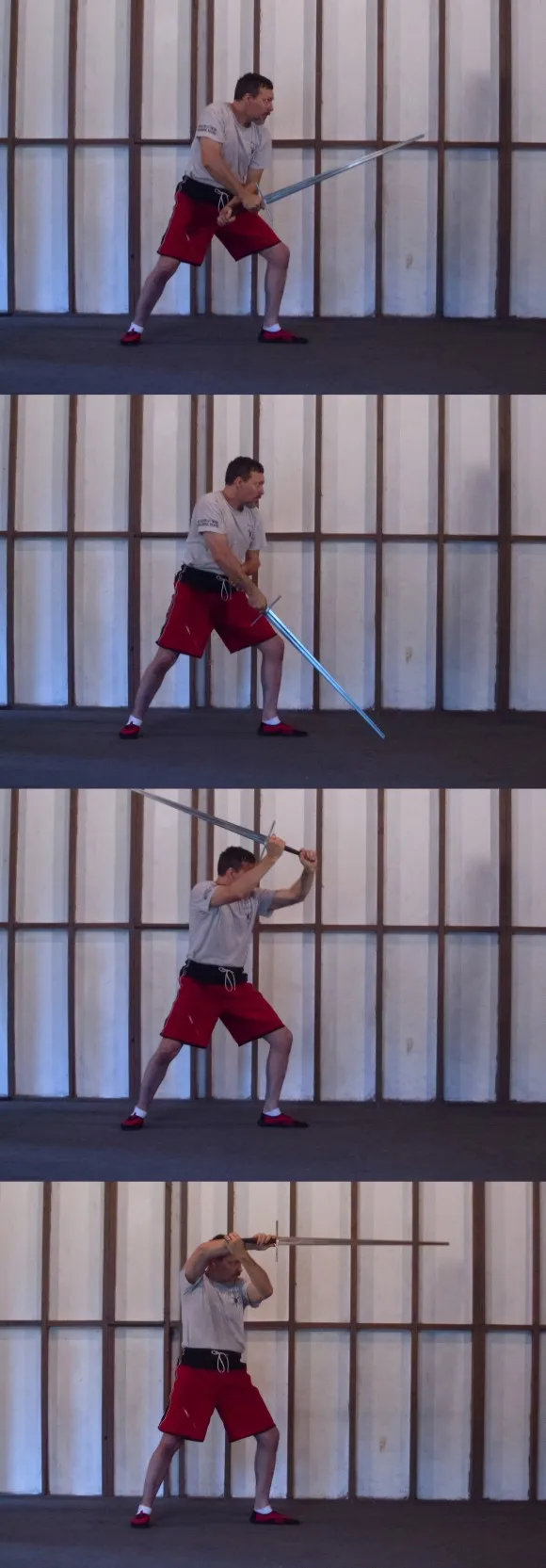

Once you're comfortable with holding the sword, the best place to start thinking about animating a swordsman is to understand the basic stances: what we call "tip progressions" or "guards."

For the purpose of our animation, information technology'due south best to think of these stances every bit our idle positions.

Every bit you begin to employ these idles, you'll notice that no affair what sequence of cuts your characters perform or what direction they face, they will ever end their movement in one of these poses. They piece of work fluidly and efficiently with each other, and they emphasize command and tactical positioning.

The four primary guards, as illustrated by John in Effigy two, are (from top to lesser) Phlug, Alber, Vom Tach, and Ochs.

Figure 2: The iv chief guards: Phlug, Alber, Vom Tach, and Ochs.

What y'all'll also find is that they play very well with your inverse kinematics rig. Like the algorithms that drive your rig, the weapon leads the motions, just like your IK target leads your animation. You lot'll also notice that the torso and arms seem to move about independently of the legs. What's more, every bit you step through the footwork, you'll find that you lot can pivot your character around on a single foot, and stepping forward or backward is a simple matter of just mirroring your animation across your center plane.

Of course, these idles require the context of the bones cuts (called "Master Cuts") to be fully appreciated. Rather than go through the entire catalogue of idles, transitions, and cuts, I'd like to illustrate my betoken with a particular sequence.

In Effigy 3, I start at the top in a fifth guard, called Nebenhut. Note how my leading leg is bent, and the trailing leg is straight. Also notation how my feet are at a 45-degree angle to each other. Allow'due south pretend that a new enemy has presented itself to my rear, and I desire to turn 180 degrees to encounter the new threat. Rather than shuffle around and swing my blade awkwardly in an attempt to maintain Nebenhut, I opt instead to hold the sword steady.

Figure three: Example of turning 180 degrees between two baby-sit positions.

As I begin to plow, my head and torso rotate first, followed by my abaft pes, which ends at 120 degrees (as relates to my left foot). On the third footstep to this sequence, I shift my weight onto my right leg, which is now my leading leg, and I deliberately bring my trailing foot to its new position. Detect that now our Nebenhut has transformed into Alber. To end the sequence, I lift my weapon out of Alber, and into Phlug.

Despite turning my entire body to face up a new direction, my correct wrist (the presumed target of our IK), never changed position. Besides, until I lifted the weapon at the end, the sword remained almost entirely motionless. Note that for my entire plough, the ball of one foot remained planted in a single position (please ignore the general position shift at step three; a wall was in the way, so I had to move back).

This theme of always returning to our bones guards continues to manifest even as we brainstorm striking. In Figure four, we see John start in a Vom Tag, and then pace forrard into a strike. What follows is a rapid rotation of the weapon to strike once more from the reverse angle. He repeats this rapid dorsum-and-forth several times, hitting at a different angle on each pass.

Figure iv: A sequence of strikes starting in Vom Tag.

Despite the change in vector for every strike, John always returns to Vom Tag before striking again. He doesn't do this because he's necessarily trained himself to perform this specific transition for its own sake; he does it because it's the well-nigh biomechanically efficient way to pass from ane strike to the side by side. This phenomenon is particularly useful for animators, because at any betoken between strikes we tin can end our sequence without popping into an idle pose, potentially jarring players out of their immersion.

Start Real, And so Exaggerate

Exaggeration is, fundamentally, i of our jobs every bit animators; nosotros brand our characters perform like an actor would perform on stage or on camera. Reality is always exaggerated or contradistinct to fit the needs of a product. But whether y'all're talking about Jade Empire or Call of Duty, you should always starting time with a solid foundation in reality. For games in medieval or fantasy settings that include sword combat, taking inspiration from the right sources (like MARE) can set your combat blitheness apart and brand the task of animating cleaner and easier.

John Clements: Give Reality a Chance

Imagine if game designers had never seen or heard of serious Asian martial arts, and never made any game with such influences. Then, i day, a budo master or kung fu skillful steps up and says, "Hey, I think y'all could make some really interesting things using our unique arts and crafts as a resource. Nosotros move in actually neat means that you lot haven't explored." I like to retrieve that game developers would quickly see that there was something significant and sophisticated there worth examining. They probably wouldn't respond with conceited indifference -- which I've seen firsthand when I bring upwardly the historical medieval combatives I report, teach, and practice.

People in The Know

I've been studying Medieval and Renaissance close combat for over three decades. I brand my living writing and researching on the discipline and operate the world's only private facility dedicated exclusively to the craft. I am no stunt fighter, costumed performer, nor showman entertainer, only an achieved martial creative person who teaches an authentic combative discipline following genuine sources. Report of these historical fighting methods is my life's passion and my career.

At present, I don't think that everyone who makes a game in a medieval or fantasy setting needs to make a 100 percent authentic hand-to-manus combat simulator any more than than I desire to see the next Call of Duty game stop working forever later your character dies for the first fourth dimension.

I do think, nonetheless, that the hardworking developers who make these games would take an easier fourth dimension (and make even improve games) if they drew from more realistic sources of inspiration when it comes to medieval combat.

The funny thing is, we already know this to be true. Only take a look at the original Prince of Persia, where creator Jordan Mechner filmed his blood brother really walking, jumping, and going through some rudimentary fencing motions equally the basis for its rotoscoped animations and action. That game was an influential breakthrough, but afterward titles would essentially copy and embellish upon those sequences, and the titles afterward that would re-create the copies -- and and then on until the insightful grounding in realism of the original source was lost.

Drawing From the Source

This process is common sense; if you are doing a modern special ops game, you consult with authorities of that profession. If you lot're doing a boxing game, you consult with a professional boxer. If you're doing an aircraft fighter game, y'all consult with a fighter pilot. If you're making a game about samurai, you certainly want to get the form and movements right by working with budo experts. When you copy the copies of copies, y'all get ever further from your original realistic base -- which ways you're adopting the aforementioned embellishments and limitations that each successive generation of copies did without looking back at the real source material to come across what your real design and blitheness options could be.

For example, a designer might come across a fighting move in a movie and remember, "This looks absurd. I wonder how I tin devise a mechanic for players to do that?" But what of the possibility that what they witnessed is mere nonsense; an inferior action the game maker is simply not qualified to evaluate? What if in that location are better alternatives? What if the "real thing" -- a general principle of self-defense force, or some element of employing a particular weapon, or a specific combination of techniques -- is actually libation? If the designer doesn't get the move from the right source, with a proper caption of how it works and why, they will exist missing out on how it fits in with the "game" of hand-to-hand combat, and won't be able to use that understanding equally inspiration for how information technology could fit in with the game they're designing.

Still this is more or less the full general process I have seen for devising archaic close combat in games, and when I point this out, developers often feel insulted. Why? Aside from perhaps offending the artistic sensibilities of designers, information technology'southward because I am suggesting that (gasp!) people who design games are not themselves also experts in the authentic sources of historical close gainsay. They have non trained long-term with accurate weapons in those methods, and they exercise not accept extensive easily-on experience in hitting realistic target materials with precipitous weapons using genuine techniques, nor do they usually fit the profile of athletes conditioned to rigorous training in armed fighting skills. It seems similar kind of a strange thing to be offended by. Subsequently all, nigh people haven't!

My chore is to understand how such weapons handle, how they're maneuvered and manipulated, how they appoint one some other, what blazon of techniques and motions the homo body is really capable of with said weapons, how physics affects melee combat, and how people respond (physiologically and psychologically) to violent deportment. The specifics often include examples of how little-known gripping deportment, armor, postures, and different footwork are all interconnected. These elements are ones I can guarantee you lot have never seen in whatever movie, Goggle box show, game, renaissance faire operation, or choreographed routine. It's this knowledge and these details which I hope to meet developers take inspiration from while edifice their own games -- instead of copies of copies.

Correcting Core Assumptions

When you develop a game combat organization or a series of gainsay animations, you practice so based upon a certain set of core assumptions: assumptions about how weapons and swords handle, about how armor functions, about what wounds could be causes, well-nigh how people respond emotionally to personal violence, how bodies and limbs react to injury, and about how existent fighters learned martial skills.

Naturally, if you're building a gainsay simulator off of a relatively shallow (or even erroneous) fix of cadre assumptions, your game won't feel right. Even if your game intends to take a more stylized arroyo to its combat mechanics and animations, however, it's worth investing the fourth dimension to sympathise how the reality of combat translates into your game's cadre assumptions, so you lot at to the lowest degree sympathise what y'all're stylizing, and why. The martial knowledge and historical gainsay skills I've redeveloped allow developers to pigment with a far richer palette of colors, if only the attempt is made to pay some attention.

Without this realistic base of operations, a video game animator ends up replicating the bad course capture of exaggerated stage combat, accepting impressions from pretend bouts with poor weapon simulators, or copying the ritualized movements of some traditional fighting mode. The consumers in turn get simplistic strikes and rigid blocks delivered from static, unwieldy postures combined with ceaseless spinning, whirling, leaping, and assorted useless (and even suicidal) deportment that defy both common sense and bones human biomechanics. Meanwhile, a wealth of more dynamic and sophisticated movements, wardings, and culling counterstriking actions from genuine fighting methods remain untapped for gamers.

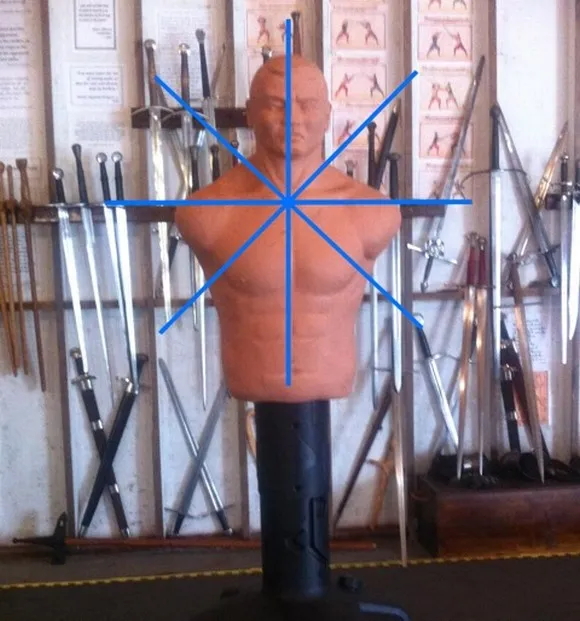

I regularly meet weapons, particularly swords, wielded by characters in video games in which the familiar figure animations and fighting motions are primitive and crude. For instance, there are sixteen possible lines of hit for the typical double-edged European longsword. Withal, players are repeatedly offered only the same standard three or four strokes taken right out of Japanese swordplay or borrowed from modern saber fencing and stage gainsay. It'southward little more than how children manipulate Nerf swords. All the various dynamic motions and distinct manners of adeptly manipulating a existent weapon -- with its wards, cuts, thrusts, slices, closures, and displacements -- are entirely absent.

Certainly, not every game with a sword needs to be a sword-combat simulator, but I am confident the software does non know how to permit players do them considering developers themselves aren't enlightened that these things are interesting -- or even possible -- in the get-go place. With a little try and attention, however, I think developers could utilise these realistic historical gainsay skills to paint with a richer palette of colors.

Devs and Demonstrations: A Mortiferous Combination

Whenever I demonstrate for game developers, the initial reaction is often merely "Whoa!" They've never seen someone move the manner I do or wield particular weapons as adeptly, and certainly not in person instead of on YouTube. And when I demonstrate that these movements are universal and apply to all weapons, whether it'south a dagger or spear or a sword and shield, something seems to click. Developers tell me, "Wow, we won't have to use the same old things again, I didn't know that yous could hold a weapon that way, I didn't know that you could strike with information technology that manner, I didn't know it was possible for someone to stride and pose in such a way, moving from one to some other in that way."

Realism doesn't close doors. It opens them. Designers can come across that with one kind of weapon, one sure type of motility tin can come after some other or that 1 movement has a counter, or a certain position tin be interfered with, stifled, or interrupted by another. Gainsay doesn't have to be the familiar "parry-riposte, parry-riposte, whackety-whack-whack, swirl-swirl" pattern.

Realism is not a dirty give-and-take for combat in fantasy games; information technology'due south a centre point from where everything can and should begin. Realism doesn't lock you in or freeze you lot in place equally a game designer. It'south an empowering tool that lets yous say, "Wow, I've got a really strong foundation to build on now." Simply once your feet are grounded in the right identify can your imagination really take off.

corbouldowelp1975.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.gamedeveloper.com/art/art-of-war-animating-realistic-sword-combat

0 Response to "I Shall Purchase a Sword and Call It Kindness Clip Art"

Post a Comment